Last week I finished the Portuguese Camino: fourteen days, 250 kilometres, spanning two countries, starting in Porto and ending in Santiago de Compostela. There are many caminos, stretching across Europe like mycelia, and most are even longer than this. They all terminate in Santiago de Compostela, a site made holy in 813 by a hermit’s discovery of bones deemed to be those of Saint James. Dazzled by a nightly shower of stars above the silent forest - interpreted as a celestial proof of sanctity - the hermit informed the archbishop, who informed the king. A citadel of churches and spires coalesced over the ensuing centuries, and drew the faithful from all over Europe.

The centrifugal force of this devotion accelerated in spite of its weak centre. The remains were, of course, unidentifiable; the hermit’s story was possibly a hoax; and a very plausible reading of the Breviarium Apostolorum - the only textual authority on the circumstances of St James’ later life and death - locates his burial site in Libya. No matter. Ostentatious feats of piety are self-demonstrative; it doesn’t matter much what their nominal object is. Devotion retains its heat. The relics were even misplaced, and their hiding-place in the Cathedral’s vast subterranean innards forgotten for centuries. They were only rediscovered in 1879.

The number of pilgrims dwindled with the wane of religiosity. But around the millennium, it picked up with speed. I met relapsed addicts, uni first-years, retirees, divorcees, mums, Germans. I met no-one doing it for religious reasons. For some it is a hiking holiday, others seek togetherness. But most people didn’t know why they were doing it - probably the ones who really needed it. Something indescribable is off; they’ve suffered a dislocation of self, of purpose, like a lodged thorn, and even if they can’t identify the source of the pain, they recognise a change is necessary.

The camino offers space. But not the sort of vertiginous, terrible expanse of unstructured solitude. Pilgrims’ routes dance around each other, so you end up seeing each other again and again, and there is a sort of unobtrusive friendliness emanating from the strangers on the way that keeps you held - a basic kindness that may never take specific form, but which at any time could.

My mind fell in with the pace of walking, set its time against the gentle drum of footsteps - which were as constant and abiding as a parent’s assurance, a heartbeat. Although the path ahead was a line, my mental patterns were cyclical. Flashes of particular memories and desires kept recurring. Dinners as a kid in France, basking in the warmth radiating from the ground after sunset, crickets and the luxurious baked odour of the grass. Riding a moped along fields and rice paddies and hills, stopping at leisure for a coffee roadside, an empty terrace facing the sky, and the sumptuousness of the freedom this entails. A favourite song, a boy, what the hell I was going to do in September. It was probably just boredom, but it didn’t feel like a drag.

Memories of travelling impressed themselves with particular insistence. Picking up my bag, which for those months was to say my life, and putting it down anywhere, a new set of people, a new set of experiences. The walk was so redolent of past journeys that I almost felt the landscape slipping into a different time and place. I felt nearer to myself at those times than myself in the recent past, like those moments were knotted together, like I had an alternate lifetime I was slowly, languidly, awakening into.

My memories wouldn’t stay down, nothing in those long empty days could keep them down, I felt they wanted to irrupt into the present and live there always. Which precisely is the luxury of long walks.

One day, an immense feeling of regret over all the things I hadn’t said or done welled up inside me with unexpected power, took over everything, metastasized into a total, objectless Regret. There is no telling what might rush in when your days are unfilled. I had to stop, have a break and a smoke, then walked with some Argentinians, talking about the Kardashians and the monarchy.

We keep ourselves in the things we love, and the way we share that love with others; the way identity and truth are wrought in idiom, and thereby enacted in real time. So being with people you don’t know, who don’t share your past or language, is at equal turns a form of release and a challenge. I could be anyone to these people. Without the support of previous encounters, you have the burden of saying entirely who you are with each new ‘hello’. But that permits you to define yourself anew, playfully, experimentally, an unlimited number of times. There is weight, and there is lightness.

When I travel, an entire history of connections, decisions, mistakes which entangle me, sometimes overtake me, are gathered into a contained weight - which I can neutrally consider, play with, pick up and put down at ease, like a stone smoothed in the palm of my hand. More often than not, you order things differently after that.

It turns out, I didn’t really have much to work through or figure out. I got that all done in the first few days. So I could spend my time concentrating on the rivers and trees.

My walk began in Porto (hungover; six hours late; blazing heat) and followed the Douro river to its mouth. Then it hugged the coastline through the resort towns of Matosinhos, Villa do Conde and Povoa do Varzim. At this point I was bored and a little disappointed by the scale of development along the costa verde, its flatness and ugliness. I began wishing evil things upon the carefree, semi-naked beachgoers bathing in sun and sea, while I trudged along like a soldier going to war, feet sore and glistening with sweat.

I did the unthinkable, and got a taxi back to a fork in the road, where pilgrims decided to either stick to the coast or walk inland. I corrected my mistake and began on the latter.

The interior of Portugal’s northern region is beautiful and intensely romantic. The more remote bits are transfixed in a state of graceful decay. The paths are fringed with anise, vine trees, and eucalyptus, and skirt tumbling granite walls in delivery to the grass. Baroque swirls of iron gates interlace with wisteria; ivy worms up through abandoned farmhouses. I passed old shrines, derelict save for the candles still lit before them, half returned to an anterior state of earthy disobedience.

The locals are warm and friendly; they never fail to nod as I go past or wish me bom caminho. I think of the salt carried on atlantic winds, the port grapes shrivelled on the vine under a beating sun, the gutterality of a language that sounds slavic. The meals are hearty, generous, indelicate. Like the stodge of mother england, designed to warm the soul after a day labouring in the cold. It speaks to an inner toughness not evident in Portugal’s sunny complexion.

The Way of St James, the spirit of itinerancy, is inscribed deep onto this people’s sense of self. One information board described the culture of Galicia and Northern Portugal as ‘Jacobean’, that is, shaped by St James. The way is punctuated by stone crosses, the ancient method of showing the next step to travelling pilgrims. The scallop shell that symbolises the camino is emblazoned on pavements, town squares, the stonework of houses, church ceilings, motorway underpasses. It is the centrepiece of their civic works. But the route itself is marked out by a curiously DIY system of yellow arrows scrawled on telegraph poles, fences, rocks, anything, like a clandestine language, a code amongst fugitives.

In Barcelos, there is an old tale: a local lass became besotted with a German pilgrim passing through; being the pious type he rejected her advances. Scorned, she planted a precious coin on him and alerted the local authorities to its theft, and having discovered the stolen coin in his possession, the local magistrate interrupted his feast to sentence him to death by hanging. The pilgrim pleaded his innocence. “Oh! Well if you are truly innocent, this roast cockerel will jump up off the table and sing!” mocked the magistrate derisively. Moments later, and sure enough: cock-a-doodle-dooooo!! The cockerel had sprung back into life. Guards were sent (too late) to cut the pilgrim down from the gallows - but the hanging rope was slack anyway: the pilgrim was borne aloft on the shoulders of St James. Thus was born the proud emblem of Portugal, and Nando’s: the rooster. I got caught up in a weird play reenactment of this story involving bits of clay and a small child dressed as a deliveroo driver. Speaking no Spanish, I had no fucking clue what was going on and missed my cue (I was the hangman).

It struck me that the camino occupied so basic and dear a place to the Portuguese that this tale would acquire a mythical status, and come to embody the nation. Most national myths become such because they illustrate some integral virtue said to be the root of their national story and character; a gallant knight, soldier or revolutionary, identified with the soul of the people. Which sometimes makes people puff their chests up and feel a spiky burning inside - when anthems are sung, at football matches or rallies. And hovering there, like the negative space cut by a silhouette, is the tacit implication that those who are not like us are excluded.

But the fundamental moral of the story of the cockerel is self-reproach. The Portuguese were mendacious and cruel. And then there is the outsider, the nameless traveller, the placeless, passing - a cavity right at the heart of their self-being. He is the paragon of christian virtue, this stranger from abroad. Ensconced in the idea of Portugal is the elsewhere, the journey, and a lack, which could be an imperative. It is a lacuna to be filled by the hope of doing better, which once took the shape of a traveller and might do so again.

Galicia had a touch of celtic weirdness. The people were a little withdrawn and mistrustful; they practice odd customs, like drinking wine out of bowls, and adhere to quaint beliefs. The whole area is swaddled by dark, potent forests, trees dripping in moss; and I imagine that on certain nights, in superstitious minds, they are still stalked by monsters.

I spent a night in a convent which was once a prison for heretics and then a boys’ school, and definitely contains many ghosts. The monk who showed us round kept us captive for 45 minutes while he shared the sum of a lifetime’s insight. Perhaps he made more sense in the original Spanish, but the translated words we got were rather cryptic. “we must learn from the turtles”; “put your hands into the shape of a book and throw it over your head”; “every morning when you wake up you must kiss yourself all over because you are so beautiful”. Well, I took on board what I could. Lastly he showed me a fountain dedicated to St Anthony, which if washed in would provide a boyfriend. Mine is still pending.

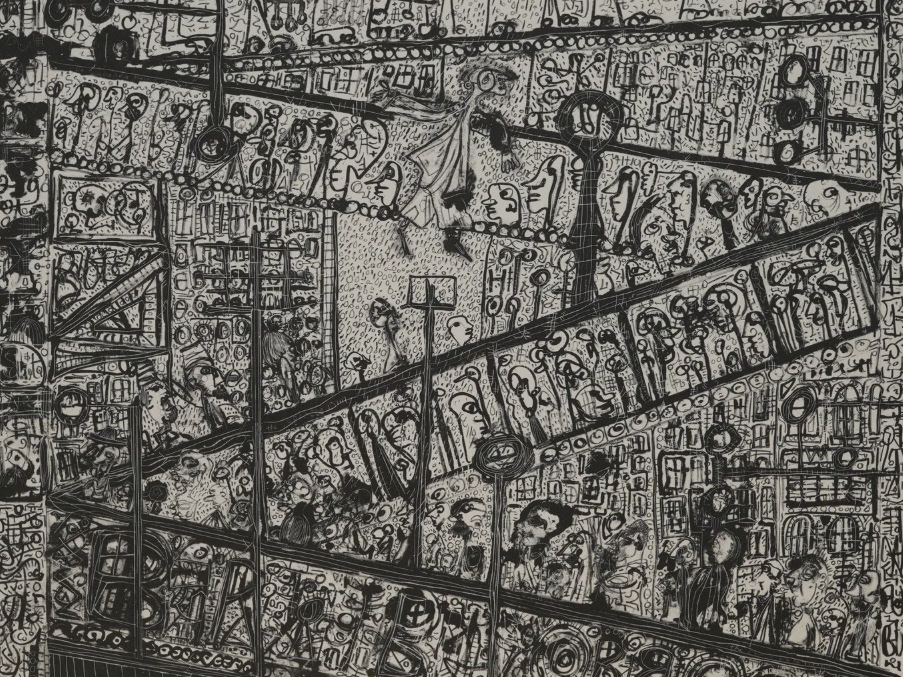

I finally hobbled into Santiago with one shoe in my hand, limping in the opposite foot to a few days before. I had suffered aches, blisters, bruises, a swollen ankle - a broken man. At the summit of the last hill was the vast edifice of the Santiago Cathedral, blazing amber in the evening sun. It was grotesquely ornate but also somehow industrial, like Wonka’s chocolate factory. Like all the other pilgrims, I splayed out on the floor of the huge square before it, staring at the cathedral, totally spent, letting the spiralling angels burn themselves on my mind. I stayed there for hours.

There was no awesome reckoning with god or self, no inner transformation, or earth-shattering realisation. I came back with much the same I had left with. I wasn’t really looking for anything more; I didn’t know what I was looking for. Which, in itself, was its own modest realisation.