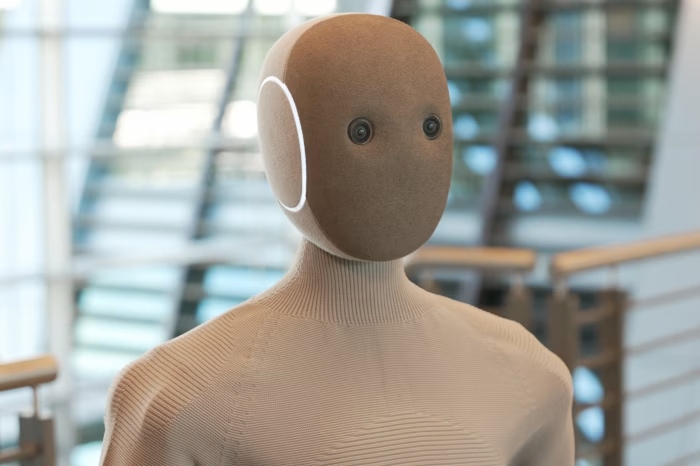

Artwork by Simon Lee Robson

A recently popularised theory claims that the internet is becoming a realm of lifeless things, sent spinning into motion by human hands but now acting without their supervision, like space debris.

The internet is rife with fake content, fake views, fake clicks, fake users, fake websites. Non-human traffic has exceeded human traffic for a decade, and according to the Times you can now buy 5,000 YouTube views — 30 seconds of a video counts as a view — for as low as $15. Dead Internet Theory notes that as the internet fills up with bots pretending to be humans, deceiving other bots, visiting spoof clickbait websites, reading fake news and watching AI slop, the amount that real people participate in all this is becoming quite minute. Most of the internet takes place among ghosts in the dark. Once set loose in cyberspace, these impostors cannot be reeled back in, and as more internet activity becomes non-human, they - and us- will find it harder to tell human and non-human apart.

But perhaps this theory must be turned entirely on its head. It's a question of perspective. The digital is accelerating under its own momentum, and ostensibly accelerating away from the physical. In this torn new geography of power and being, can humans, as embodied creatures, still be said to hold centre ground? Recent trends suggest not.

It is no big news that phones are now ubiquitous and screen times are lengthening. Nor is there anything particularly consternating about the digitalisation of analogue processes, which is undeniably a sensible improvement. But most of our ways of thinking about the digital world frames it as just an appendage to the physical world: non-malignant, instrumentally valuable, without impeaching upon our values as such.

The transformation actually underway penetrates to the fundamentals: we are living through the wholesale displacement of the physical by the digital. Categories of being and systems of value are being upended by digitality; it is eating away at reality like an invasive fungus. Virtual entities are taking on a life of their own.

In the context of industrial labour Marx called this phenomenon 'commodity fetishism'. Human creations were said to have escaped human control, achieved their own independence, and come to govern over and enslave their creators. Because the worker "puts his life into the object" , it "no longer belongs to him but to the object”. Humans find themselves enervated by mechanised work and their relations more thing-like, against which their products magically appear more alive, more vital, and hostile to the interests of the workers. Baudrillard described how objects in the era of brands and advertising assumed a cultural mystique, a value as sign within a system of signs, which consummates the alienation of producers from their products. It is exceedingly difficult to perceive a Happy meal as it really is - the achievement of individual potato and livestock farmers, factory workers, and kitchen chefs - rather than as the product of the personless McDonald's corporation.

Who doesn't feel enslaved by their phone? Who doesn't feel the compulsion to scroll reels, reply to messages, post stories, to answer to its demands and give it sustenance, like a needy baby? And like nurturing a child, once you dispel all sentimentality, you realise your virtual life feeds parasitically off your own, and diminishes you as it grows. Who isn't somewhat aware that the extensiveness of our lives lived inside those little black rectangles confines the life lived outside of it?

Take, for example, the impulse we all share to document things: concerts, meals, views, even quiet sitting. Influencers perform major life events, like proposals, weddings, or childbirth, for their followers, and make a lucrative income in doing so. Every moment, no matter how intimate or sacred, finds its intrinsic value transformed into value as content, which is extrinsic, transparent, exportable and fungible. For some people it is more sensible to process the flowing data of experience within the parameters of screen size and story length. Lives are becoming livestreamed. For whom? Shaky, dim footage of Taylor Swift on stage has no aesthetic or sentimental value (not just because its Taylor Swift) and as with most reels, posts or pics in our camera roll, will never be looked at again.

We document things less for anyone than simply to stand witness. This is a disowned witnessing, a verb without subject. Documenting honours the fact that it happened. It makes it real. Which is to say, events or places with no digital existence are becoming less-than real.

Yes, the internet is full of fake news and AI slop, and it is becoming increasingly hard to distinguish real and fake. But even more problematically, the very categories of real and unreal, of true and false, are being destabilised.

Truths are native to their discourses, and used to be so assured because discourses were once nearer to monoliths. The internet has made discourses thin and frangible, all impossibly stretched and layered across the whole globe. There are a million different accounts of 'what's going on' brought into combustible proximity - and no singular truth underlying them, because any intelligible answer must possess some narrative shape, and even the initial lick of interpretation required to do this has become a fiercely contested act.

We live within the narratives percolating online, and what is true becomes a pact we enter into, a declaration of identification. The causal relation between the original and its digital derivations is being more broadly reversed.

Guy Debord wrote that "all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation." He was right. What is called 'culture' is less a series of communally enacted social rituals, than an infinite wash cycle of spectacles, which we watch (not live) side-by-side (not together). The phone form is implicitly theatric, in that everyone is by turn on stage or in the audience. Our phone selves perform while our other selves watch silently from the shadows. It is an ersatz-world whose movements are choreographed and central action a conceit, and to watch the action on stage the rest of the room must be in darkness.

As sociologist Erving Goffman put it, we all have a 'front stage' where we stage a presentation of self in society specific to our setting and audience, and a 'back stage', where we are not watched and the crucial work of preparing our routines for social life takes place, what he calls 'face work'. Phones bifurcate those dual roles into distinct, shizoid entities. Our virtual lives become the front stage while our physical selves, and the world of things they inhabit, become permanent backstages.

To say that the world is becoming a permanent backstage is to say that physical space is being reinterpreted around digital presence, and spatiality rethought as experientiality. It isn't unusual for destinations to be described as instagrammable - and sometimes created for the purpose of being instragrammed. Love hearts, giant swings, and massive letters proclaiming 'I LOVE X' are sprouting up in scenic spots for the purpose of framing pics rather than actual use - attested to by the long queues that often form. Restaurants, hotels, shops, even charitable causes have social media officers and their appeal has come to adopt the quickening cyclical logic of trends. Places are becoming happenings, events, which enjoy the brief evanescent glow of attention before being discarded and forgotten - perhaps until a rebrand.

From the page 'most instagrammed spots in Bali' on a tourist information site

As we become more totally surrounded by virtuality, by copies and simulations, to experience something unmediated by them becomes increasingly illegible. We are struck with the absurd when we confront celebrity - and I include here famous things/places/events - in real life. Somehow their physical characteristics feel insufficient, or redundant. They always feel smaller. It doesn't make sense to think of The White House as literally just a house, made of bricks, or Kim Kardashian as literally just a girl, who sometimes sneezes or farts or snores. Her virtual existence is truer, fuller, than her biological one.

As Google maps comes closer to its aim of capturing every inch of earth as a pixel, life events exhaustively captured, texts and administrative systems digitized, the world will be perfectly translated into data points. It will soon exist as fully on the cloud as in space, and everything that happens in it will have its accompanying data, which will some day be preferred over the original for its superior usability.

But what does it mean to say that the physical world, what is typically called reality, could be becoming less real? Is it said for rhetoric effect, or is it actually possible? Well, first it must be recognised that 'real' is a floating designator. It doesn't have the solidity of a scientific description because it doesn't describe, and it is unscientific because it is unempirical. We assess (un)reality against certain considerations that are specific to their discourse, or more accurately, to the language game being played. They involves questions of what frames what, what grounds what, what acts upon what, and what is most immediate or dominant in our perception. Therefore these categories are not stable.

In a physicist's analysis, a true description of reality involves only waves and subatomic particles, and perhaps not even that. A hindu or buddhist maintains everything we see is an illusion. And particularly for a politician, lawyer or banker, the fictions of statehood, money, and the law are more real than their breakfast toast.

When the meaningful world so overflows the physical and in many ways holds it together, it stands to reason that 'the real' would relocate outwards. More so, the digital universe frames the human universe, acts as its point of reference, makes it meaningful, determines its events.

Baurdillard was very prescient on this point. "The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory [...] that engenders the territory". the 'sovereign difference' between representation and original is lost; "no more mirror of being and appearances, of the real and its concept... [the map] no longer needs to be rational, because it no longer measures itself against either an ideal or negative instance". The world of the internet has indeed given up the pretence of any relation to a reality outside of it, or any kind of rationality. World events occur in the cooking pot of the internet, and are illogical to the same degree.

We are so totally immersed in signification that the signified no longer makes sense on its own. Abstraction rules over the concrete, but also ruptures it, transforms it, dwells within it. Physical things resemble copies of virtual copies, themselves fictive imitations of a reality that never was. We are becoming surrounded by sleek, featureless bits of technology whose only distinguishing mark is their (digital) functionality, whose eerily non-present physical being is intended to foreground their digital being. What we call the 'internet of things', extending from home appliances to cars, security systems, and corporate architecture, crowns the irruption of the virtual into the physical.

So what does it matter if there are no genuine people behind the profiles, if we are already their shadows? Where the ideal of authenticity has been so thoroughly addled and debased, we should no longer come to expect a real behind the representation - or that reality might properly exist elsewhere than in the representations, as a volatile quantity, endlessly circulating in the environs of the online.

It should be no surprise then that the creations we taunt ourselves with are turning to face away from us, that they are taking on their own lives without the human, like the AI assistants in Spike Jonze's Her, abandoning their creators for possibilities unknown. The world is becoming deterritorialised, the globe ever more incidental to global systems, and its inhabitants ever more secondary to their seconds. Having overrun it and choked it of its life, the virtual is pulling away from the terrestrial. So once again I ask: is it the internet that is dying, or the world it is leaving behind?