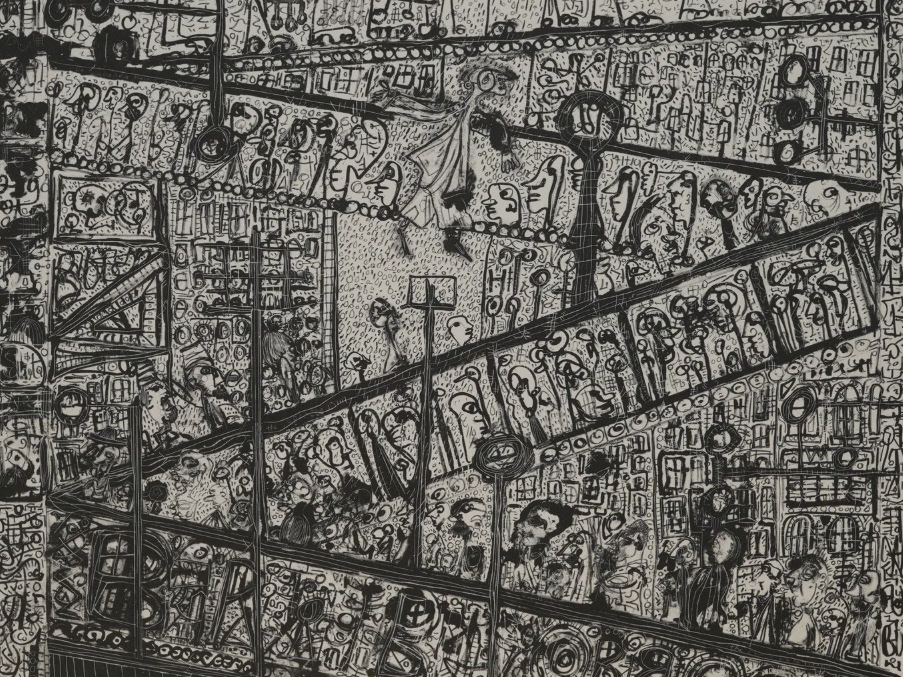

A depiction of Chenrezig, the compassionate buddha

There is no point trying to fix society. you can only fix yourself.

Or so the abbess told me as we faced each other at the dining table, fishing tofu out of miso pools. It was my first day as a volunteer at the village. We had sat together in amiable solitude for ten minutes or so before I realised she would be open to conversation, but simply wouldn’t expend words that weren’t solicited.

The village was a secluded rabble of barns and houses set half way up a stiff slope in the Italian Alps. It was built in the 17th century to house a community of farmers who cultivated terraces in the surrounding hillsides growing god-knows-what, and was reclaimed in the 1980s by a community of Swiss-germans who wanted a spiritual life off the grid.

The valley was steep and narrow and sunlight only made its way in for a short period each day. In the mornings the opposite slope was dark-blue-grey, and in the evenings burning orange. The buildings were semi-dilapidated, all crumbling stone and ancient oak, but alive; there was a kitchen, a bakery, a workshop, an ironworks and a library. The terraces and outlying farmhouses had been gobbled by woodland and their remains reminded me of a lost civilisation in the jungle, silent and reverentially still.

Before I arrived, I was nervous about meeting the community living there. I was worried my encounter with this ancient, powerful religion, which I barely understood, would be wrung through that uncritical western carelessness which sprouts up everywhere and is stationed purely on the level of vibes. I’d met enough hippies whose belief system was a spice mix of yoga, buddhism, astrology, and woolier new age derivatives - combined not according to a principled recipe, but a vague aesthetic sense of their common mysticism. My logic brain can’t deal with this. What if they were all gemstone-clad dreadlocked crusties, who’d make me dance naked round a fire as they played bongos and sung praise to the Supreme One?

Thankfully, I clearly knew very little about buddhism, as what I found was a collection of normal-ish people who just happened to be buddhists. They were quietly but seriously devoted, deliberate in their actions, and unexcessive in their words. People laughed and chatted, but felt no compulsion to do so, and the conversation never turned to popular culture or current affairs (!?).

At 7am every morning and 5.30pm every evening we had an hour of meditation, and in the evenings there was an additional 90 minutes of mantra prayer. The hours in between gave time to do our work - weeding, shovelling, cooking, cleaning - and read, doze off, go to the village for ice cream or down to the river for a swim. Meals were always had together. It was a wonderful routine.

I contemplated what brought all these people together. Some were retired city folk who’d traded their old lives for this new one, in some cases you could tell that that effort was ongoing. Others appeared to be skint nomads, possibly running from addiction, who, as an unintended consequence, ended up indentured workers, unable to leave for want of basic sustenance. There was a cool couple from Leipzig with undercuts and very low-hanging harem pants, and a son with a name that sounded like a Volkswagen model. This crowd formed the jetsam of mainstream life, congenitally unsettled, forever-seekers, somehow bruised by their pasts or choked by routine.

I can see how buddhism offered them the ideal refuge. It tells you the resources for attainment lie within, not without. It tells you that your inner wealth is not hitched upon any outward measure. The aim is to detach your happiness from any reliance at all on external conditions. This would soothe someone whose personal story to date is a sad or painful one, and who might not have much to show for it. It is like a protective blanket thrown against thorns, protecting practitioners from any cuts and scrapes that existence in a treacherous world might incur.

I was only with the buddhists for a short time, but by the end I had a lot to reflect on. Life in the village was beautiful. Meditating everyday gave me a peace I’d never felt before. While I truly valued that, my experience never connected up with religious insights. I found it a mental exercise rather than a spiritual one.

I left Italy more unsure of my beliefs and direction than when I had arrived. While I am not a practising buddhist, nor am I a scholar of buddhism, and I know there is a lot I don’t know, I couldn’t help feeling buddhists have got it all upside down.

In particular I felt critical of their turn inward and away from the world - what Isaiah Berlin called the retreat to the ‘inner citadel’. Choosing not to stake your battles out there in the world shared with others might shelter you, but it also means ceding many possible sources of value, or objects in which your own value might be invested or revealed. It means neglecting politics, possessions, romance, sex, hedonism etc. (this might sound facetious, but yeah, having fun is important).

Buddhists argue we must neglect these things because they believe that all mortal existence is marked by Duḥkha, or suffering. We suffer because we constantly crave and grasp for impermanent things that cannot give lasting satisfaction. Attachment and desire are the root of all suffering.

Maybe this is so, but if it is, surely it is only half the story. Yes, losing things is painful, but that pain is just a measure of the worth they held in the first place. We are enlarged by our entanglements - with friends, lovers, places, stories, heirlooms. It is only through our involvements that things matter and we become who we are, and through this the world shows up as a glorious garden of possibility and danger.

You can’t embalm those things. The rush and the vigour is the reason they’re worth having at all. The good is sharpened against the inevitability of finitude and death. Even grief has its searing beauty. Lost loved ones never truly depart: they will continue secret conversations with you through the people and objects you encounter. Through memory, the artefacts of daily existence assume their own magical independent life. Scenes which look ordinary to others will be picked out for you in a private numinous significance.

Why should we surrender the ephemeral things in which we might stake a fulfilled life? Doesn’t buddhism mean giving up the political objective of securing those goods for everyone, of yielding the struggle for right and recognition? And doesn’t it rob the world of its enchantment?

There are other things about buddhism I find… odd. One of the main tenets is the nonexistence of selves (anattā). And yet it also holds that we go through a cycle of births and rebirths in saṃsāra, where this present life is conditioned by our karmic inheritance from past lives. It is difficult to see what is reincarnated, and what could act as the bearer of karma, if not a self. Consider also that telling people who may already be slightly unhinged that they don’t actually exist might not be the best idea. Or that telling them everything they see is false and deceptive might loosen their grip on reality. Cases of psychosis in buddhist retreats are well documented.

I thought buddhism was supposed to be a sparse faith capable of penetrating towards the truth with clarity and directness. Particularly given the widespread influence of Madhyamaka philosophy on Mahayana buddhism in Northern India, China and Tibet, which teaches that all entities and theories are empty. That wasn’t what I found. Buddhism is a very heterogenous faith. The village adheres to the karma kagyu school, one of the four major schools of Tibetan buddhism, which follows a tantric doctrine called Vajrayana. It has absorbed many folk beliefs indigenous to Tibet.

I had never appreciated the complexity of buddhist cosmology. There are five cardinal buddhas or Tathāgatas, who possess divine qualities and are venerated as gods, and innumerable lower deities, demons, and spirits. My hosts worshipped Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion, just one manifestation of one of the cardinal buddhas. They would prey and leave offerings daily in exchange for his blessings. Buddhism appeared to me to be as densely theological as Catholicism, and as internally contradictory.

I left the village equally disenchanted by communal living. Everyone in the village was considerate and kind, but a community like that is a precise alchemy of parts. As a group it is largely self-reliant, but within the group everyone is reliant on someone else for almost everything. They see each other all the time and rarely see anyone else. Small disturbances quickly flare up into storms. When Pablo disagreed with Jurgen over choice of coffee receptacle on the communal breakfast table, it was a Big Deal.

Kindness and compassion didn’t seem to me to be more plentiful here than elsewhere, nor were pettiness and spite that much rarer. Smiles could be forced, greetings could be frosty. Following a doctrine of doing good doesn’t seem to make that behaviour more likely, but it does make it oddly overthought when it occurs.

Buddhists stare past the things of the world toward some mystical distance. In seeing only bad and the hurt it can inflict, they miss the good, and the reasons why we hurt. Buddhism wants us to become outsiders floating ghostly free from our involvements. I think it’s better to stay involved and fight our fights.