Attention is today’s most coveted resource. People crave it. Companies compete for it. We expend it with little discipline or discretion - and yet so much escapes it.

There is simply too much sensory information for the brain to process at any moment in time, so in order to make the world manageable and to facilitate meaningful action, our brains screen out much of reality. Only stimuli that is deemed potentially relevant to our present aims and concerns makes it from our sensory receptors to the higher cortical centres in our brains. (If you don’t believe how much your brain will suppress when concentrating on a particular task, watch this video of basketball players passing a ball.)

And now, more than ever before, there is sharper competition to capture that small modicum of attention anyone is able to give. Our phones are nodes in an infinite network, opening onto an abundance of small packets of dopamine laid before us like seeds sown in a field. Tiktoks, stories, ads, apps, likes, comments. The real world commands a diminishing presence in this ever denser perceptual landscape - and even that is plastered in signs and symbols.

Most of the world, most of the time, passes below the line of conscious appreciation. So what about everything that includes? Everything that is habitually passed over unnoticed and unseen?

The Art of the Unseen

T.S Elliot called art a “raid on the inarticulate”. Art gives shape and resolution to ideas and emotions that are dimly sensed and can only be rendered in language clumsily. In that sense, it illuminates what is hidden.

But usually only to an extent. Artists often seek to attract, concentrate, direct, subvert, or disperse our attention. When we regard their art, they hold us captive. We are made to look - and at certain things. In this sense most art does battle with all the other stuff vying for our attention. But some modernist artists in 1950s America refused these terms of engagement. In 1951, the artist Robert Rauschenberg exhibited a series of blank canvases consisting simply of a thin coat of white house paint

Robert Rauschenberg, 1951

Where is the viewer supposed to look? Nowhere. But this does not mean the artwork holds no potential value for them. These featureless paintings are curiously animate, under the play of shadows and the changing light conditions of the day. The composer John Cage said of White Painting: “[the] subject is unavoidable (A canvas is never empty.); it fills an empty canvas”.

I’ve heard art be described as a dialogue between the artist, the artwork and the viewer. At its worst, art can be moralising or didactic. Rauschenberg has decided to exit the conversation, or perhaps take the role of listener. In refusing to enclose or direct our focus, the artist frees the viewer for an unbounded exploration. This total withdrawal of intention or authority gives space to the hidden, and the viewer is given possession over the artwork in the fullest possible sense. The viewer is taught to see again - and see attentively. A quiescent beauty hides in the lines, shapes and sounds around us. Through this exercise the world is revealed.

Cage took great inspiration from Rauschenberg’s investigation into nothing. In 1951, the same year Rauschenberg created White Painting, Cage visited Harvard’s Ancheoic Chamber. This was a room designed to trap all sounds made with it, the quietest place on earth. But rather than pure silence, Cage was met with two, almost imperceptible sounds: a high one - which was his nervous system in operation - and a low one - his blood in circulation. He realised absolute silence was an impossibility for any living, flesh-and-blood being.

A year later Cage would compose a piece, 4’33, consisting of no notes. Widely renounced as a joke or an affront, Cage said the piece was misunderstood: it enlisted ambient sounds and the rare opportunity of captive attention to make salient those events which are passed over unnoticed: the patter of rain, a breeze, breath, rustling clothes.

Musicologist Daniel Charles likened 4’33 to a Duchamp-style readymade: it makes art out of what appears artless: silence, or more precisely the ambient sounds found in an environment. Due to Cage’s lack of interference in the piece, Charles argues it is less music than a ‘happening’, in which the composer is more actor than musician.

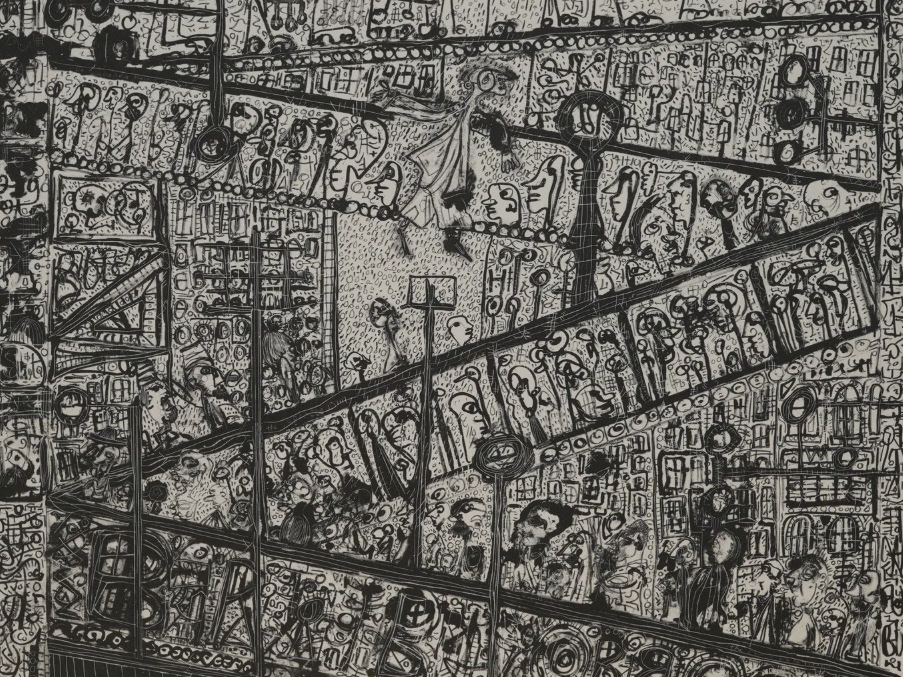

Similar to Duchamp’s found objects, Rauschenberg made a series of artworks he called “combines” over the decade following his White Painting: mixed media pieces that assembled found objects into a sort of three dimensional scrapbook. They are bewildering, orderless mishaps, in which the familiar is glimpsed and then lost. The eye doesn’t know where to look.

Rauschenberg, 1954

Cage writes:

This is not a composition. It is a place where things are, as on a table or on a town seen from the air: any one of them could be removed and another come into its place through circumstances analogous to birth and death, travel, housecleaning, or cluttering. He is not saying; he is painting...

This is art without message or intention. Where the artist abdicates his unequal position in defining an artwork, the viewer is released to encounter the work in novel ways. Attention is suffused across an entire scene. For Cage, this unguided exploration is a form of play, of entertainment.

“Beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look [...] Is when Rauschenberg looks an idea? Rather it is an entertainment in which to celebrate unfixity”

The Hiddenness of Things

Rauschenberg and Cage sought to explore how art without a fixed outline of purpose or intention might reveal what was previously hidden. They weren’t the only ones intrigued by the question of what our attention leaves behind. Purpose-driven action, and that which eludes it, are both phenomenologically rich areas of investigation that preoccupied the minds of philosophers such as Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty. Once we step away from our preconceptions about a stable external reality and squarely consider the embodied, inward feel - the is-ness - of attentive action, there is clearly much at play.

For the most part, we are entranced by our present concerns and objectives. When we are not on our phones, this might be making dinner, writing an email, kicking a ball. When we are drawn all the way in to the task at hand, the world around us disappears. The things we use lose their properties in geometric space, and gain a new significance in terms of the complex of possibilities they hold forth and their propensity to aid or frustrate our immediate goals. A path of action is ‘lit up’ for us by these entities which guide action, Merleau-Ponty writes, “as notices in a museum guide the visitor”. They immediately summon forth the appropriate response from us without any intervention from the will or the intellect. We don’t decide to act; we just do.

Merleau-Ponty contrasts objective space with this lived space: a tactile universe of possibilities structured by our skills, purposes, and the lay of our environment. A chess player doesn’t see 32 wooden pieces of x weight and y height, but a series of moves and possible counter-moves. My phone is not glimpsed as a metal and glass object, but as an opening onto digital horizons. Objects are most useful when they are invisible in this way; useless things recede into an altogether different kind of non-presence.

In this way the world is polarised into things ‘lit up’ by their significance in the present context, and those things that have no significance, which sink back into inconspicuousness. Both positive and negative aspects of this polarisation are necessary to enable fluid action - otherwise we would be immobilised by an overabundance of signification; our attention would be stretched too thin.

So what of things our attention must leave behind? When objects become useless to us, they fade into a sort of penumbral haze, a blanket of vagueness where no determinate features can be picked out. We don’t notice this, because to notice is precisely to snatch something back into the light. And it isn’t just useless things that reside here, but most of the world: higher calculus, cloud formations on Neptune, train times in Mumbai, the migration patterns of birds. Anything on which our attention is not concentrated in that moment. As Heraclitus wrote, nature loves to hide.

The hiddenness of things, for Heidegger, is the cornerstone of their reality. Being is essentially self-withdrawing and self-concealing. Things habitually lurk in a dark, shapeless tangle; they have no meaningful presence for us, they do not figure in our world - not even as a theoretical postulate, a negation, or a ‘known unknown’. Indeed, the notion of concealment rejects the commonsense idea that entities, as we understand them, can perfectly exist independent of our understanding.

Heidegger says entities get “snatched out of their hiddenness” when they show up meaningfully, as this-or-that entity, and become available to enter into various kinds of relation with us. This includes the straightforward cases of knowledge, belief, or sensory perception, but also more basic, embodied relations: in skirting round a chair, handling a gearstick, avoiding a topic of conversation or eye contact with someone in a crowded room, something is unconcealed.

For Heidegger, concealment is the basic state of entities; the uncoveredness of anything is always a “kind of robbery”. He takes his cue from the ancient Greek word for truth, alētheia, which combines the word for ignorance or forgetfulness, lēthē with a prefix (a-) indicating privation. Lēthē, incidentally, is the name for the river of oblivion in Hades.

This can be quite baffling for a culture used to defining falsehood negatively as the absence of truth. But think about it: before anything is known, it is unknown. And things are constantly escaping back into obscurity. We are always forgetting things, facts, faces, just for them to momentarily resurface, dredged up from the subconscious - and soon return back to the river of oblivion. As the psychologists attest, conscious awareness only ever shines its light on a minute portion of reality at any one time.

Heidegger describes Lēthē as a dark forest encircling a clearing, and human awareness as the light that shines down through that clearing. It reveals a meaningful world, structured by purpose and language, where reality is articulated into concepts and things. But things are constantly falling back into darkness. Where attention fails, the forest closes in.

The Nothing

So what lies out there, in the wilderness beyond objects? Well, there are no ‘things’. So there is no-thing - there is Nothing. And no, this isn’t a cheap play on words. Heidegger describes Lēthē not just as a dense forest, but also as a vast ‘open region’ beyond the borders of our delimited practical world. It is a vertiginous expanse, an excess of being - that is simultaneously nothing at all.

Nothingness, generally speaking, is considered a sort of aberration of grammar. When we say “there is nothing”, we are not describing an object called nothing, but signifying the lack of any objects. But for Heidegger, the Nothing is a real phenomenon, that we can encounter directly.

Heidegger marks a distinction between the beings that populate the world, such as birds and bees and trees, and Being itself: that by virtue of which any of these beings exist - the very act of their existence, their sheer is-ness. It is this primitive sense of Being that Heidegger co-identifies with Nothing. An undifferentiated presence might as well be called an absence. And it is thanks to this fundamental ‘space’ or nihility that entities can emerge as meaningful at all. To emphasise the dynamic, constitutive activity of Nothingness, Heidegger says rather obscurely: “the Nothing Noths”.

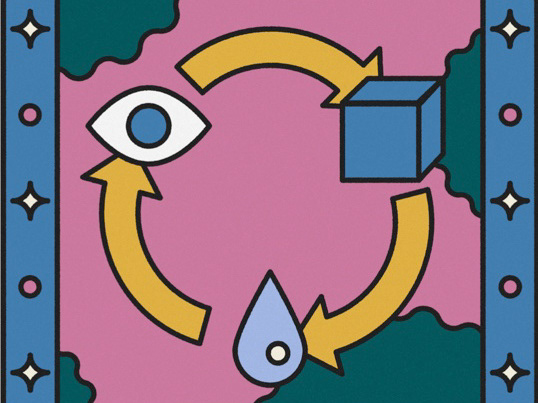

The open region of the Nothing is what Zen Buddhists call the Field of Emptiness (kū no ba). This is the stage of higher perception on which entities are revealed to lack substantive independent existence, and are at the same time revealed to causally depend on each other, and so be deeply interconnected. All things are ensnared in the same endless web of causal relations, therefore all things interpenetrate one another. Huayan Buddhists illustrate this with the image of Indra’s net - infinitely large and set with jewels each so dazzling that every other jewel is contained within its reflection. Cage was aware of these ideas, and sought to explore them in his compositions.

A visual representation of Indra's Net

The Nothing terrifies when it is momentarily glimpsed from within the bustle of life as the desolate outside, vast and unending, where all meaning or purpose falls away. But it can also present hope. A culture’s aims and ideals ossify over time into a fixed matrix of categories that can entrap and suffocate us; we have little freedom in how we might interpret ourselves and the world. The Nothing is free of all that. Since it engenders and harbours determinate being, it is the wellspring of all possible action, and since it is prior to any cultural structuring, it contains an inexhaustible reserve of possible ways of being. Therefore it holds forth the prospect of true freedom.

The Practice of Emptiness

It may sound strange, but if we tie the threads together, we can see that a movement toward this authentic freedom might begin with useless things.

As I said previously, the things we use are unconcealed for us. We are usually so caught up in our daily tasks and projects that we forget about what is unnecessary. We struggle to fix useless things into a concrete plan or scheme, and we sometimes find it hard to mentally file them as ‘this’ or ‘that’. They tend to flee our attention and stay hidden.

Useless things can be an escape point from the concretion of socialcultural norms that both delimit and act through purposive action. As Daoists keenly recognise, they can offer a pathway to encountering the field of emptiness. The Chinese terms for useless, wuyong, and non-wilful action, wuwei, both contain the prefix wu, meaning empty. The Daodejing discusses how absence (or formlessness) is a necessary complement to presence (or form) for the creation of the useful. A jug is formed out of clay, yet its hollowness is what allows it to be useful. Similarly, a room is constructed with four walls, yet its open space is what makes it useful.

Just as Daoism courts useless objects, it encourages us to become ‘useless’ people. In renouncing goal-oriented action, we release ourselves from the brunt of our concerns. Laozi writes that the wise man wanders where “there is no door and no house”; he is “directionless”.

But the Dao master is only ‘useless’ in inverted commas. While his life is no longer stratified into an infinitely receding series of objectives, by effecting a withdrawal of self (and that self’s future), the master finds stillness and presentness. Paradoxically, total emptiness is complete presentness. If we empty ourselves, we are filled by the world. Daoists often invoke the image of the mirror. Zuangzhi writes that “the Perfect Man uses his mind like a mirror - going after nothing, welcoming nothing, responding but not storing”.

The more our presence is an insistence, the more we are subject to resistance from a world that is insensitive to our designs. But through surrendering the will and forgetting our separateness, and going along with the natural direction or Tao of the world, we can achieve an artful communion with our environment. It then becomes unclear whether I direct the work, or if the work directs me. Zuangzhi has an example of a cook cutting up an ox by moving his knife through the spaces already existing between the joints. As if by itself, Zuangzhi writes, “flop! The whole thing comes apart like a clod of earth falling to the ground”. Indeed, nirvana originally meant ‘fading out’.

Western cultures, which have been built on a metaphysics of essence, will struggle to get past our scientific worldview and see reality as anything other than a set of self-enclosed objects interacting causally, like billiard balls. Western ontology is structured into binaries that reverberate throughout its material works: presence/absence, inside/outside, man/nature, dominant/dominated. In Western architecture, art, even cuisine - as well as in its conceptual systems - there is an impulse to put things in boxes and keep them separate.

East Asian cultures on the other hand are rooted in a metaphysics of emptiness. They do not rush to a category, nor seek to exploit the tension between extremes. They effect a softening of distinctions, an un-bounding of identities, a withdrawal. The boxes are undone.

East Asian architecture, for instance, does not try to storm our senses with bold façades. Buildings do not announce themselves. Traditional Japanese homes consist of a series of rooms and corridors woven around gardens and courtyards, where space is divided by a series of simple rice paper partitions and can be redistributed easily by moving the partitions about. It is an architecture of lightness and impermanence. Thinner, translucent panels, called shōji, suffuse the interior with a featureless muted glow, creating a delicate atmosphere of absence - quite unlike the harsh outside light that streams in through glass windows and dramatically illuminates the dark. Entranceways slide open and rooms open up onto spacious verandas, upsetting the distinction between inside and outside and precluding any attempt at a solid demarcation between the two.

Japanese rock gardens (sekitei), a constant feature of Zen temples and a popular enthusiasm for Japan’s warrior class, consist simply of raked gravel and a sparse smattering of rocks. The architect and sekitei expert Mira Locher observes that any space demands a contrast between positive and negative aspects to give it shape and dimension. While in the west, boundary objects such as columns or shrubs are considered the positive element, in the east it is empty space. Emptiness itself is the material the gardener shapes with his arrangements. In turn the garden helps the viewer to empty themselves.

___________________________________________________________________________

Most of us are each so enrapt by the spectacle of the things before us that we have lost the eyes to see. It is right that Heidegger speaks of unconcealment as a kind of theft, but we would do well to consider who is made poorer by it. We often speak of attention being given or grabbed, and this distinction is insightful in stressing the violence with which certain stimuli blot out the world. We must step outside the activity of our lives to invite an encounter with that banished, terrible beyond. This must be more than a merely aesthetic experience, since that condenses things into an impression. Rather, we are required to simply dwell with the being of things.

Oddly enough, there are parallels between doomscrolling and the absent dwelling-alongside-the-world that Daoism extolls. When we doomscroll, we aren’t imposing a scheme of action or pursuing a set of objectives. Actions are unconsciously summoned up from us by our phones: we open an app before we know we’re doing it, check Hinge five times in a row, while away an hour on tiktok without realising. We let ourselves be effortlessly carried along by the world, like water in a stream, just as Daoists propound. Passively navigating the digital space ghostlike, we turn our presence as much as possible into an absence. Are brainrotted tiktokers unwittingly following the way of the Dao?

There is one major distinction. Unlike the world, which is subtle and withdrawn, our phones are saturated with things seeking our attention, things calculated precisely to be most likely to get it. It is a sensory dumpster truck. The reason we glide across this flood of stimuli is because we are constantly pulled onto the next thing, drawn by the unknown. Our attention cannot linger and settle on one thing because it has so many possible objects, so any one object is unable to hold our attention.

The Dao master, on the other hand, is attuned to that which doesn’t seek our attention, nor gives itself over easily. Their attention has grown to fill the entire world; it is an objectless openness. This is what would the brainrotted would so sorely benefit from: to sit still and see, without looking.